The Woodland Classroom

THE WOODLAND CLASSROOM

(Chapter 15 in Crafting: Transforming Materials and the Maker, Radically Redefining Learning.

Published 2019 by Hands On Press)

The gate to the primary school where I work once a week in rural Herefordshire is locked with a keypad. Recently they were told they had to invest in this expensive gate and device in order to meet Ofsted requirements. The fear is of ‘stranger danger’. Teachers and parents who have forgotten the code to the keypad, frustrated by this unnecessary 8 foot tall obstacle, climb over the traditional stone wall that runs at a height of around 4 foot either side of the gate. The children and staff here are lucky, in most other schools the 8 foot tall fence extends all the way aroun their school.

Our task, as educators, is to prepare the inner as well as the outer landscape – to prepare the ground in which the seeds of inspiration can grow. The essence of this preparation is trust in those around us, not fear. As Maslow explained in his pyramid of learning needs, at the bottom of the pyramid there must be safety, we must feel safe in order to be able to learn. Safety and trust are therefore the ground of education.

At the centre of a healthy educational landscape there must be a warm centre. This is a place where the day, session or class begins and ends. Ideally there would be a hearth fire in this place, perhaps a circle of logs to sit on, but if not, a symbolic candle, or simply a stone or another natural object to gather around. This hearth creates and provides a safe, calm ‘container’. It becomes a container ready to be filled with creativity.

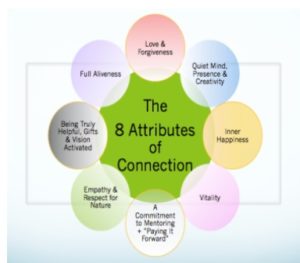

The hearth is not only, or exclusively, a physical place. To encourage a feeling of safety there is a need to create a sense of connection. This connection ultimately needs to function on three levels: connection to self, connection to others and connection to the natural world – both around and within us.

The renewal of these connections can take time. The outdoor educational landscape provides many of the qualities required to rebuild them. The journey can be begun simply by a verse or a song. A pause at the beginning and at the end of a lesson can bring time to reconnect with ourselves, internally.

A brief word from each participant and from facilitators can bring hearts and minds together, to facilitate cooperative learning. A moment to listen can remind us of our senses and the gateway to connection with the natural world. Alternatively an introductory game can be used as long as it leaves everybody feeling seen and heard…valued. This vital element of building self-esteem and thus allowing learning to take emerge has long been overlooked in our society: the knowledge that we all have a unique part to play in the creation of a world in which we want to live. The word ‘hearth’ includes the words ‘earth’ and ‘heart’: two words whose value is often overlooked in our modern world.

An established outdoor educational landscape may have more than one hearth. Or a main hearth might be established and then satellite points of stillness identified around the site. If there are different craft workshops on the site it may be that each workshop takes a moment to create a metaphorical centre before beginning work by using a verse or a song.

The word ‘hearth’ also conjures up an image of elders around a central hearthfire, be it in an old stone cottage in the British Isles or around a fire in the desert on the other side of the world. The elders help to create a calm, safe place. Their presence emanates wisdom and experience, and whilst they may or may not contribute practically, their knowledge is always ready to be shared. Sometimes it is not possible to find a human elder willing to be part of a modern educational landscape. In the absence of human elders the ‘other-than-human’ world can be acknowledged and called upon. An introduction to ancient rocks and trees on the site may be appropriate. Or we may need to call on the elder within each of us, or on our knowledge of our ancestors to support our work. The important thing is to create a feeling of support, a feeling that someone, something, some entity, has ‘got our back’ and is encouraging the work we do in a broader context.

Change and flexibility are of paramount importance for human development, however, young people need an anchor, a rhythm on which to balance a healthy ability to develop. Without this there is more pressure on the nervous system. More stress is created by needing to re-adjust to new situations every day, or every forty minutes (the length of an average school lesson).

Adrenal fatigue has become an epidemic in our modern world (Dr Peatfield research)1. Young people and adults are in a state of alert, constantly activating the ‘fight or flight’ response. This puts pressure on the nervous system, drains the immune system, results in widespread insomnia, depression and lack of motivation when the body is only occasionally allowed to fully relax.

Today, many people grow up without a sense of place and home. Families do not pay much attention to moving house, moving areas, moving away from friends and relations. With fewer stable families, school is often the one constant in a young person’s life. Within school very little consideration is given to ensuring pupils are in a relaxed place where they can learn. The emphasis is on delivering the lesson rather than noticing the underlying causes of pupils’ ability or inability to pay attention.

The content is often superficial and without a meaningful context. I was recently asked by a parent to help her find a way to deliver some Forest School sessions as part of flexi-schooling. She felt that the sessions had become little more than duty, her son was bored and disengaged. The tasks given for one three hour session such as “identify some local trees in the area” could have been made meaningful if they had been ‘allowed’ to cover ten sessions. If there was time for her son to learn to make something from wood or learn about which wood burns well on a fire, practically using his own hands, gaining his own experience, no doubt he would have felt invigorated, inspired and confident instead of just bored.

Over a longer period of time a natural rhythm can be found in which there is time to ‘be’ instead of to just ‘do’. Natural rhythms are inherent to creating with our hands, especially if the whole process can be incorporated. For example, if children are set the task of carving a butter knife from hazel the following can be experienced; a breathing out time is spent whilst they look around the woodland to find an appropriate branch, sawing the branch is an activity which engages the whole body’s rhythmic system, sitting and whittling to create the shape absolute focus is required which calms the ‘monkey mind’ and allows the breathing to settle into a more regular rhythm. After their initial haste the children learn how to take off less and less wood at a time, how to gain more control to give a subtler finish. How desperately our modern world needs speed to be replaced with subtlety and sensitivity!

Working with the seasons provides a natural rhythm for learning. For younger children especially, and increasingly for children of all ages, seasonal activities are extremely beneficial. Just the practicality of teaching young children to dress themselves for the different seasons all year round provides a whole range of learning opportunities. This is so not just for the children, but for their parents as well, many of whom do not venture outdoors for any amount of time if the weather is cold.

The weather, especially with its unpredictable nature in this country, ensures that any outdoor learning environment teaches flexibility and resilience. Very young children are masterful teachers at making the most of any weather: muddy puddles turn to skating rinks in winter, dancing autumn leaves fall to form a soft winter bed, sleeping bulbs bring colour and joy in Spring.

Spaces that can be warmed by a fire (always a wood burning fire/stove, for which the children must be involved in the gathering and preparing of the wood) and have some separation from the wind and cold are perfect as they allow the rhythm of outdoor activity to be balanced with calm slowing down, even during the colder months.

The key to rich and meaningful learning is to ensure, as part of the educational landscape, that the pupils are consistently exposed to the elements. In this way they can come to know and love the variety of rhythmical changes. This builds physical strength and stamina, of course, but also, emotional intelligence.

The weather changes in this country can be helpful as a backdrop to the language of emotions. The weather can change here as often as our moods do. Being active in all weather allows children to acknowledge and experience their full range of emotions, and then to begin to step back and watch the waves ebb and flow. Children do not really need their elders to pass on the knowledge of facts and figures; all these can be obtained from the internet with ease. What they do need is guidance in building relationships (with themselves and others), in true, face to face communication and honesty.

The rhythm of the day and the night can also be extremely beneficial if one is able to incorporate it into the educational landscape. The evening offers a gentler time to share stories and face truths with the shadows of the night and without the need to show all hidden places of the soul on faces lit with sunlight. The moon and stars offer perspective on many human problems. The warmth of a campfire draws people together, without the need of social norms or rules that can be complicated and threatening for many. People gather together to keep warm in the forgiving light of a fire that is forever transforming and burning away what is no longer needed.

From my own experience of living off-grid in small spaces I know the benefits of incorporating regular exposure to the elements as a necessary part of living. I know how I will delay chopping and sawing wood, or taking a trip to the outdoor kitchen, or going outdoors to check the ropes holding a tarpaulin in place on a windy night, or even walking the dog on a day of cold, driving rain….and I know, that every time I notice the resistance and complete what needs to be done, my sense of wellbeing returns. My belly softens, I breathe more easily, smile gently and find my place more easily in the community of life. To find a way to include these practical daily tasks in an educational landscape is essential. One small step outside the box of comfort and incipient negative perspectives brings boundless rewards. This small step often requires creative thinking in order to resolve a practical challenge.

It may be part of our challenge as educators to prove that we are achieving numerous aims and objectives, to be able to meet our learning outcomes. However, surely the more vital challenge is to equip the children with creative minds that can solve future problems we cannot yet imagine.

I had the pleasure of spending time with the Bushmen of the Kalahari recently. In an environment that looks positively sparse compared to our own lush, fertile country these peaceful people gather and hunt, no longer to survive, but to create. As part of The Living Culture Foundation, they are creating an educational landscape for those of us who have forgotten the opportunities of living with very few belongings.

Their tools consist of a simple knife, an adze, a bow and arrow and a set of sticks to make fire. The women make jewellery from ostrich egg shells. Shaping them with a hard flint like stone and rounding them by sanding a whole necklace of beads on sandstone. A leather cape serves as a baby sling, a pouch for gathering plants and a mat to sort the beads. Fewer material possessions nurture our creativity.

In the Kalahari the children play games with balls of earth and whatever scraps are left behind by careless tourists. They are opportunists. They sing and clap and dance and smile and laugh a lot. Many thousands of years ago, despite the hardship of surviving in the desert, they spent time finding and processing pigments to paint pictures about the life they lived. It seems that they know that humans cannot live without creative expression – a fact that many in the Western world seem to have forgotten at a great price. A lack of creativity leads to increasing levels of stress related disorders, depression, violence against fellow humans and suicide.

If the outdoor educational landscape is developed Nature ‘does the work’, she absorbs excess tension, calms heightened energy, relieves tired teachers, parents, children allowing for more facilitation and less stockpiling of facts. Natural beauty is soothing to the senses: calms tired eyes, lightly brushes the hardened touch, delicate smells and a symphony of sounds.

The outdoor educational landscape is rich in any natural setting and enhanced by the presence of running water in which to play and learn and cleanse, clay and mud to model, sand to sift, trees to climb, gardens to grow, willow to craft. The presence of animals to nurture and the construction of craft workshop spaces are, of course, part of the ideal educational landscape. These have been discussed in detail in previous chapters.

The shift towards a truly educational landscape – within and without – is more urgent than ever. Without it, attempts to encourage lifelong learning and the learning of ‘life skills’, the realisation of “a positive contribution from every child” (Ofsted guidelines, Every Child Matters2), fall on barren ground.

I was recently offered the use of a 22 acre woodland for my work. The site had been lived in and cherished some years ago. Walking around the woods I had an overwhelming sense of sadness. I really felt that the woodland was lonely without the interaction of a family and meaningful human activity that had previously been part of its life. Around the same time I visited a grove of trees in a field with a central old oak. This site had been used as a site of celebration four times a year for the last fifteen years. The positive feeling of vibrancy and nourishment was tangible. The natural educational landscape not only offers and opportunity for us to learn and grow it also offers a chance to notice that whatever we do actually matters, affects the world around us. The ripples of our actions give new meaning to the idea that we must ‘leave no trace’ in any natural environment.